In Germany, the Zettelkasten method is not so well known, although its creator (surprise!) was German. His name was Niklas Luhmann and he was a sociologist. Note boxes are a method of organising knowledge and putting what you have read and learned into context.

Luhmann wrote over 90,000 index cards (slips of paper), gave them an index number and put them in a physical drawer. I don’t want to explain the system any further here, as there are countless essays and videos on the subject. Especially in the English-speaking world, “Zettelkasten” is currently experiencing a real hype – not least due to programmes such as Obsidian, Notion, Logseq etc.

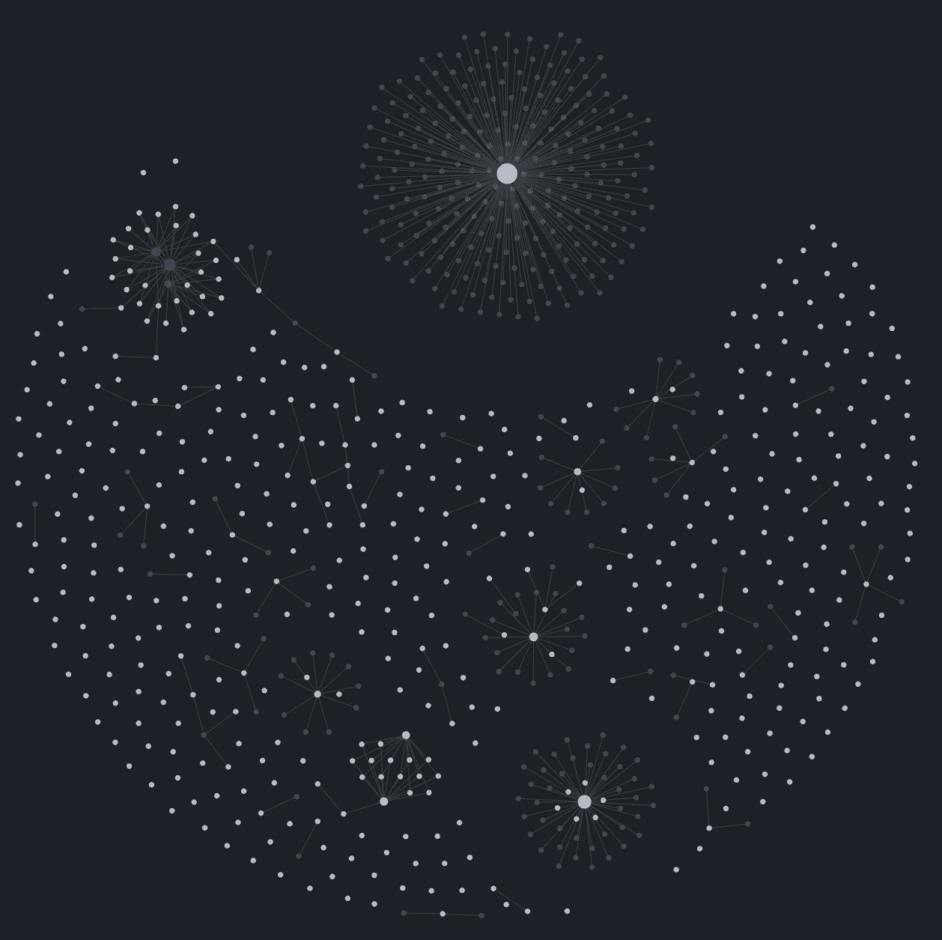

In principle, Luhmann created a note for interesting content in books, ideas, quotes and thoughts and linked related content. This resulted in literature notes and permanent notes with summaries in his own words. This way of working also means that you have to deal with different pieces of paper again and again, thus deepening your knowledge. Today we would call it a database with hyperlinks.

Notepad for bloggers and content creators?

I’ve spent a lot of time looking into this over the past few weeks, thinking about what the note box method could do for bloggers, content creators or for my job. Spoiler: Absolutely nothing!

I realised that a lot of people are interested in it and have tried to use “Zettelkasten” profitably for themselves. After all, the inventor of the Zettelkasten, Luhmann, has published 58 books and countless articles thanks to this method. Once you have filled the note box well and organised it into literature and permanent notes, all you have to do is reach in and the next book practically writes itself. At least that’s the theory and hope that makes notebooks so attractive to many people.

This method can actually be helpful if you are collecting information on a specific topic with a specific goal – for example in research or if you want to write a book on a topic. Perhaps also if you have ONE big hobby and want to record and consolidate your knowledge.

However, if you are dealing with many different topics that mainly come from digital sources (which can certainly have overlaps and similarities), a card index is an unnecessary and overly complicated way to get back to the analogue past, which is also hardly usable for third parties.

In my opinion, Zettelkasten is also not a tool for knowledge management. Rather, it is there to structure and deepen a specific topic. As soon as many differenttopics are involved, card indexes are useless, except for additional effort.

Luhmann did not have access to the possibilities that we have today with wikis or apps such as Obsidian, Loqseq, Notion, etc. It was still a world in which knowledge was disseminated and recorded on paper. So he would either have had to tear pages out of books, physically copy them, cut them to size and glue them in, or he could immortalise fragments of them in his notebook.

Today, we can copy and paste any content, photograph it or save entire books, papers, websites and magazines as PDFs and make them searchable.

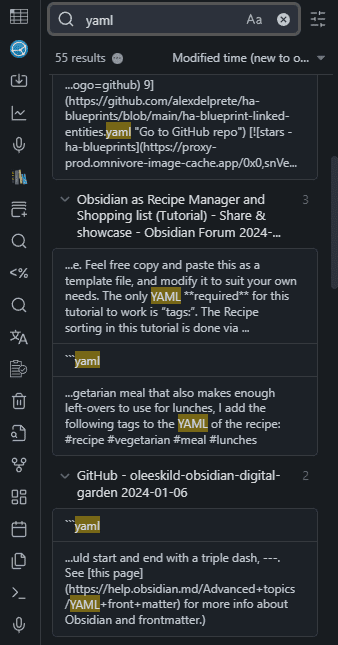

Note boxes are nothing more than the linking and summarising of notes and annotations. In Obsidian, you can use links, fuzzy search, tags or simply keywords and folders. For example, when I research topics on the subject of Home Assistant, the individual notes are given the tag “HA”. Topics such as Docker or backup also come up in Home Assistant. These can be easily linked to existing notes.

Luhmann couldn’t just say to his cupboard: Give me all the cards on topic XY from the last 2 years. In the digital world, this is a basic function. He was condemned to give all notes an index and to reference it at least once in another location. Otherwise he would never have found anything in his 90,000 notes.

Reasons why many fail with the note box

If you follow the discussions in various forums, on Reddit and in the Obsidian forum, you will realise that many people fail to implement the note box method. It often results in unnecessary work without bringing any real added value or gain in knowledge. Many try almost desperately to apply the method, fail and wonder what they are doing wrong.

You’re not doing anything wrong: note boxes are simply a method

- that is currently being hyped

- is only useful for a few users

- comes from a different era,

- and may still seem most suitable for research and narrowly defined topics.

Today, a digital note can be as long as you want it to be and you can change, add to and expand it as often as you like. Obsidian plugins can automatically generate tables of contents. Dataviews automatically and dynamically generate connections and create context. Once you have such an extensive note, Obsidian makes it easy to divide it into smaller topics or vice versa.

- Für iPad Pro 12,9 Zoll (3. und 4. Generation), iPad Pro 11 Zoll (2. Generation), iPad (6., 7., 8. und 9. Generation), iPad Air (3., 4. und 5. Generation) und iPad Mini (5. Generation) , iOS aktualisiert auf 12.2 und höher

- Nutzt die Apple Pencil Technologie, sodass Sie ganz natürlich schreiben und zeichnen können, ohne Angst zu haben, einen falschen Strich zu machen. Mit Scribble können Sie Ihre Handschrift sogar in Text umwandeln.

Luhmann even wrote his notes on very thin paper to save physical space in his boxes (and his office). With giga- and terabytes of cheap storage space, this doesn’t matter today and you have the luxury of being able to save the complete source.

For digital tools, linking content is a basic function. It is usually pointless to try to transfer an analogue workflow 1:1 into the digital world, which many card index fans do almost slavishly – including index numbers, highly complex templates, etc. I often get the impression that it’s more about implementing Zettelkasten by hook or by crook because it’s chic and trendy.

That’s why I use Obsidian with links, tags and dataviews where it makes sense. But not every note has to be linked to another, which it can’t do anyway with my many interests and topics. Obsidian’s excellent search function brings up the content that is relevant – without any time-consuming reworking with “literature notes” and “permanent notes”.

My alternative to the note box: the big screen

When it comes to a topic for which I am collecting more extensive content and sources, I throw them into a file and make my annotations and notes there. This creates a better and faster overview than the “atomic” information units (Fleeting Notes), which only have to be summarised into larger information units afterwards. In Obsidian, even headings, bulleted lists and sections can be referenced – if necessary.

A lot of questions with the note box method revolve around how to deal with the many small notes, where to save them, and so on. With one large file per topic, this problem is solved before it arises. Give each entry in it a creation date (can also be automated), have Obsidian generate and update a table of contents from the headings and you’re done!

Only the really relevant content goes into the large note. I make stupid notes and not smart notes. The only important thing is that I make them quickly and easily so that I remember them and have to find them again.

I don’t organise much here either, and if I do, then only at a later date. Once you have a significant collection of content, you realise:

- What structure makes sense for meaningful organisation

- How much of it is already outdated and can be deleted

So don’t worry about what the ideal future folder structure etc. would be beforehand, but decide on it when it can and must be decided.

Many notes are also superfluous insofar as you can google much faster and more up-to-date. I don’t need to have them in my own “database”.

The most important functions that note-taking software must have:

- You have to have it easily and quickly available (mobile!) and be able to use it

- It must have an excellent search function

- The content should be saved in a format that does not depend on the software (which is why I like Obsidian and Markdown so much)

Self-optimisation, PKM and data hoarding

The topic of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) must also be viewed critically:

Data-hoarding is a problem that many face. Especially in the course of the self-optimisation craze, everything is collected, assigned tasks, noted, sorted, prioritised, etc., come hell or high water. This means that relaxed reflection falls by the wayside.

But that’s exactly what’s important when you’re looking for ideas. That’s why they tend to come to me in the shower or on the toilet 😉 and rarely at my desk. Boredom is almost a guarantee for new ideas.

Some people spend more time optimising and maintaining their PKM system than creating their own content from it. I collect information in order to turn it into an interesting blog post, not for the sake of collecting it.

A lot of content is already outdated after a short time and can be googled better, more up-to-date and faster. That’s why many of my notes have an “expiry date”. Notes that I have made on a certain application version, for example, are probably outdated after 2 years and are then also deleted.

When I moved my notes from Evernote to Obsidian, I took the opportunity to do an extensive clean-out. More than half of the content created in almost 15 years of using Evernote could be deleted without hesitation as it was outdated or no longer relevant.

And that brings us to …

The Collector’s Fallacy

The collector’s fallacy describes our tendency to collect and archive information without actually learning or internalising it.

The notepad, but of course also Obsidian and other programmes, tempt us to collect and hoard every scrap of information. One day it will come in handy – the main thing is not to lose it.

We feel rewarded when we collect things, be it physical copies of texts or digital bookmarks. A bulging note box or obsidian vault with lots of links looks impressive and was a lot of work. That’s why it has a certain value for us.

The problem is that just collecting information is not the same as actually understanding and applying that information.

- Examples of the Collector’s Fallacy:

- Physical copies of texts: students often copy many texts but do not actually read them. The stacks of copies become an alibi that pretends they already know the content.

- Digital bookmarks: We save interesting web pages as bookmarks, but that doesn’t mean we’ve really understood the content.

- Why does this happen?

- Collecting information is easy. We immediately receive physical or digital copies as a reward.

- We condition ourselves, much like Skinner conditioned pigeons: When we click “copy,” we immediately receive stacks of paper or digital bookmarks and notes. This also makes us believe that we have done something useful or important.

- Why is this a problem?

- Real knowledge requires that we integrate information into our own knowledge.

- Simply discarding things does not lead to progress or change.

Conclusion

For Niklas Luhmann, the card index was an analogue way of preserving his knowledge and it was a method that worked for him in a world of paper. However, his high output of books, publications etc. was certainly not due to his Zettelkasten method. It was part of his personal way of working and his discipline. At the time, however, the method was certainly remarkable and revolutionary.

Today, notetaking apps almost automatically help to connect content with each other. This goes far beyond what Zettelkasten was and is able to do, because the apps can find connections that we would never have thought of ourselves. At a time when we are bombarded with more and more information, this is necessary.

You can even integrate ChatGPT into Obsidian, which can find topics across the entire Vault, summarise them and provide suggestions and correlations. With one click, you can create a nicely organised note from these findings, which (hopefully) provides real insights. Luhmann would probably have been delighted and might have written 100 books with it.

That’s why the Niklas Luhmann Archive page ends with the following:

‘Using the multiple-storage principle and the referencing technique reminiscent of hyperlinks, Luhmann thus simulated a modern, computer-based database system as early as the 1950s, despite the analogue storage technology.

Niklas Luhmann Archive (niklas-luhmann-archiv.de)

I am convinced that Luhmann would simply use software like Obsidian today. If only because he could always have his notes with him. This was not possible with his wooden box and he would have had to spend less time managing his notes.

Letzte Aktualisierung am 2025-12-14 / Affiliate Links / Bilder von der Amazon Product Advertising API

Leave a Reply